It is difficult to watch someone you care for go through bouts of pain. It also can be difficult to forsake precious time you could have together because your loved one is sleepy or “out of it” as the result of taking pain medication. But keeping patients comfortable and free from pain sometimes involves accepting trade-offs. It is the patient who ultimately must decide about his or her priorities in the last few weeks or months of life. At a time when so little is in a patient’s control, honoring his or her decision about how to spend what time is left and how much pain to endure is crucial to kind and meaningful caring.

Managing pain

- Accurately describing pain

- Medication

- Myths and facts about pain medicine

- Non-pharmacological approaches

- Tips for working with medications

Contact Us

Fill in this form and one of our caring staff will get back to you.

"*" indicates required fields

Accurately describing pain

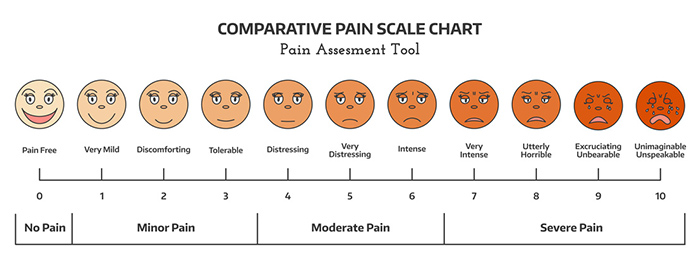

The simplest way to communicate about pain is to give it a score from 0 to 10, with zero representing no pain and 10 referring to excruciating or unbearable pain. Somehow assigning a number helps both the patient and the physician put the pain into an easy-to-understand perspective.

The simplest way to communicate about pain is to give it a score from 0 to 10, with zero representing no pain and 10 referring to excruciating or unbearable pain. Somehow assigning a number helps both the patient and the physician put the pain into an easy-to-understand perspective.

Many caregivers are surprised to discover that the person they care for downplays pain in front of the doctor. Even when they are asked a direct question about it, many patients deny having much pain, when in fact they have been experiencing significant discomfort or distress. A variety of reasons could explain their response: They value being stoic; they don’t want to be a “difficult patient”; they fear that more pain means the disease is getting worse; or they don’t know how to describe what they are feeling.

Other information that will help the doctor includes the answers to these questions:

- When did you start feeling this pain?

- How often do you experience it during the day?

- Where do you feel it (what part of your body)?

- Is it a burning pain? Aching? Shooting? Throbbing? Stabbing? A steady sensation of pressure?

- Does it seem to have a pattern (i.e., it comes on at a certain time or after a certain activity)?

- How long does it last?

- What has helped relieve this pain? Does anything make it worse?

- How has this pain been affecting your daily life? Your activities? Your relationships? Your mood?

Medication

Using medicines is the most common strategy for relieving pain. Over-the-counter choices include aspirin, ibuprofen, or acetaminophen; doctors also prescribe pain killers such as morphine. These stronger types of medication, known as opioids, are available in several forms: pills, liquids, patches, suppositories, pumps that inject a small quantity under the skin, and fluids that are delivered through an IV.

Although prescription medicines are very effective, they often cause side effects. Consulting with the patient’s doctor will help identify the type of medication and dosage that will work best, but pinpointing the best solution may take some trial and error. Following is a list of the most prevalent side effects caused by opioids and things you can do to help the patient relieve them.

Constipation is quite common, as is nausea. However, some medications and home remedies help relieve these problems. (See our article about Caregiving Tips.)

Another side effect is involuntary twitching of muscles. This condition seems to be more distressing to family caregivers than it is to the patient. However, some medications can offset this response, or a different version of the morphine could be investigated.

Many patients feel very sleepy, especially during the first few days after an increase in dosage. Once the body adjusts to the new level, the patient usually becomes more alert and able to interact. If this does not happen, you may wish to talk to the doctor about trying a different medication or perhaps prescribing a mild stimulant to counteract the patient’s drowsiness.

Many patients feel very sleepy, especially during the first few days after an increase in dosage. Once the body adjusts to the new level, the patient usually becomes more alert and able to interact. If this does not happen, you may wish to talk to the doctor about trying a different medication or perhaps prescribing a mild stimulant to counteract the patient’s drowsiness.

Similarly, some patients respond to pain medication with symptoms of mental fuzziness, confusion, or delirium. If these responses do not resolve in a few days, the patient may want to try a different medicine.

Just as morphine slows down many other bodily functions (e.g., digestion), it also slows the patient’s breathing. If a patient is near death, slowed breathing may hasten the moment when he or she stops breathing but will not cause a patient to die who would otherwise have lived. The patient’s wishes are of prime importance. For this reason, it is important to talk to family members and the doctor to let them know if keeping the patient pain free is more important than helping him or her live a few hours or days longer.

Return to topMyths and facts about pain medicine

Many patients and families have inaccurate notions about prescription drugs that relieve pain. “Palliative care”—the medical discipline of making comfort a priority, especially at the end of life—is a relatively new field. As a consequence, people often make medication decisions on the basis of an incomplete understanding of the issues. Following are some of the most common myths about the use of opioids for pain relief in the seriously ill:

Many patients and families have inaccurate notions about prescription drugs that relieve pain. “Palliative care”—the medical discipline of making comfort a priority, especially at the end of life—is a relatively new field. As a consequence, people often make medication decisions on the basis of an incomplete understanding of the issues. Following are some of the most common myths about the use of opioids for pain relief in the seriously ill:

Myth #1: Fear of addiction or dependency. Addiction is a physical and psychological dependency on a substance. When people worry about addictions, they often conjure images of desperate, hedonistic individuals who behave in irrational and illegal ways in order to get a “fix.” People who take morphine for pain rarely become addicted; they don’t fit this picture. For instance, patients in hospitals who are given unlimited access to a morphine pump following surgery typically undermedicate themselves. It is extremely unlikely that a patient in the advanced stages of a terminal illness will develop that type of desperate physical/psychological dependence. Unfortunately, a fear of addiction often results in family caregivers not giving the patient enough medication, which leads to the patient experiencing unnecessarily high levels of pain.

Myth #2: Fear of developing a tolerance. Some people are concerned that if the patient takes pain medication too early, the body will adjust (i.e., develop a tolerance) and need increasing dosages to get the same effect. Although it is true that dosages must be increased, this fear is based on an assumption that there is a ceiling on the amount of medication a person can take. Fortunately, there is no ceiling, so there is no need to endure pain in the present in order to save the medicine for some future need. If the symptoms increase, whether from tolerance or increased intensity of the disease, the dosage of the medicine can be increased indefinitely. Typically, if current dosages are no longer effective, then the amount must be increased by 25 to 50 percent. To say there is no ceiling does not mean there are no side effects, however. Increased dosages may well increase the number or severity of side effects. But if a terminally ill patient wants to be pain free, there is no need to put off relief early in the disease as an investment against potential pain in the future.

Myth #3: Concern that increased pain means the disease is getting worse. A person might experience increased or decreased pain for a variety of reasons. In the case of a tumor, it may simply have shifted and is now pressing on a different set of nerves. Or, psychological circumstances may have changed and altered the person’s perception of pain. For instance, relatives who were visiting have had to return home. Without the pleasant distraction of their company, the patient is more aware of physical pain and discomfort. No matter the reason for increased pain, if the patient does not communicate this change to the physician or family caregivers, he or she is not likely to experience relief from the symptom.

Return to topNon-pharmacological approaches

Heat or cold. If a particular area of the patient’s body is painful, hot or cold compresses may help relieve the discomfort. Ask your doctor which is most likely to be beneficial. A hot bath can help, but heat can also be applied through electric heating pads, hot water bottles, microwavable pillows, or gel packs. Be sure that the heat source is wrapped in a way that will protect the patient from leakage and burns. Heat therapy is best if it is applied for 20 minutes at a time. If the person you are caring for is undergoing radiation therapy, do not apply heat to that part of the body.

For some types of pain, 15 minutes of cold is a better source of comfort. Ice packs, gel packs, towels soaked in ice water, or a bag of frozen peas all make excellent cold compresses. As with heat therapy, be sure the source of the cold is wrapped to protect the patient against leakage or skin irritation.

Massage. The healing power of touch has been recognized for millennia. Massage stimulates blood flow, encourages relaxation, and increases the recipient’s feeling of well being. Great benefits can be obtained by light stroking, kneading, and rubbing. Seriously ill individuals may need the massage to be gentle and restricted to areas that are not red or inflamed. You may want to use lotion to reduce friction on the skin.

Relaxation techniques. With techniques such as deep breathing or progressive relaxation, the patient can interrupt the cycle of pain-fear-tension-more pain. Deep breathing is simply slow, deliberate inhalation and exhalation of air, with an emphasis on the release of tension with each exhale. In progressive relaxation, the patient tenses and then releases various muscle groups along the body. By contracting muscles and then relaxing them, the patient experiences the contrast and learns to identify and deliberately release tension in the body.

Mental techniques for pain relief. Like massage, meditation has long been recognized around the world as a method of releasing tension and easing pain. There are several types of meditation. Some forms focus on expanding the mind’s awareness beyond the level of the individual. Others concentrate the mind’s awareness on the internal functioning of the body, which, surprising as it may seem, reduces pain by placing the focus directly upon it. Either method seems to be helpful.

For those who are not inclined to meditation, guided imagery is an effective way to draw upon the mind’s ability to transform the perception of pain. Guided imagery usually entails someone giving the patient instructions in a calm, low voice, describing images and sensations such as a sunny day on the beach, with the gentle suggestion that each wave is washing the tension and pain out to sea.

A slow, detailed narration of this type can help the patient by focusing attention away from the pain and onto pleasant and relaxing images.

Adjusting our attitudes. The experience of pain involves the mind’s perception of a physical sensation. Our mind, including our attitudes and the focus of our “inner voice,” can deeply influence our perception of that sensation and the degree of hopelessness we may feel about it. By using the technique of “reframing,” a patient can maximize the ability to cope with pain by altering any limiting or destructive messages to the self. For instance, “Nothing has worked. This pain is never going away,” can be reframed to “I wish I were not in pain. I guess I need to keep experimenting so I can find the right combination of approaches.” Reframing includes the practice of intentionally shifting the awareness from what isn’t working to focusing on whatever positives do exist in the situation. It challenges all-or-nothing thinking. Thus, another way to respond to hopelessness about pain would be to transform “This is useless, nothing has worked” to “This isn’t working as well as I had hoped, but ‘X’ has helped a little, and that’s a start.” Difficult as it may be, if the patient concentrates on what truly is working and gives him or herself encouragement to move forward, it will ultimately be more productive than focusing on disappointments. Focusing on defeats causes a person to be more aware of pain than if the focus is directed to victories or what might be possible.

Counseling. Although pain itself is very real, our perception of it and our confidence in our ability to cope with it have a significant impact on how much we suffer. People in chronic pain are not able to be themselves. They are constantly distracted, often irritable, and frequently discouraged. Relationships can become strained, and the person’s self esteem can plummet. Physical pain often brings with it emotional, spiritual, and social pain. Some patients find it helpful to work with a counselor trained in pain management techniques. These professionals can help not only with coping strategies to offset the physical pain of illness, but also with suggestions for handling the complicated feelings and dynamics that often arise when a person in pain is dependent on others for help and support.

Distraction. In the context of childbirth, Dr. Ferdinand Lamaze discovered that the nerve pathway that sends messages of pain to the brain can be filled with other nerve messages, effectively distracting or blocking the brain from fully registering the negative sensation. The Lamaze method uses unusual breathing patterns coupled with intense concentration to distract a laboring woman from the pain of contractions. Although “labor breathing” may be helpful for short term, stabbing, or shooting pains, it is not generally a long-term solution for chronic pain. Nevertheless, the distraction principle is a useful one. Certainly a patient with nothing else to focus on is more likely to be fully aware of his or her pain than is a patient whose attention is drawn to a specific activity. Depending on the patient’s energy level and mental capacity, useful distractions can include singing, playing cards, listening to music, watching television, talking with friends, reading, or having a story or magazine article read to them. Be aware that when distraction helps, it does not mean the pain was not real to begin with. Distraction simply blocks the pathway of the nerves leading to the brain and, thankfully, keeps the brain from registering discomfort.

Prayer or spiritual support. In times of pain many people turn to prayer or spiritual pursuits and find it a source of great solace. Because physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being are interrelated, if the person you care for is spiritually inclined, the use of prayer, the reading of spiritual works, or talking with members of the clergy may indeed result in feelings of reduced pain or anxiety.

Acupuncture. The Chinese have a long history of using acupuncture very successfully as a method to block pain. This ancient method of healing is based on a concept of “meridians” or pathways that circulate vital energy, called chi, throughout the body. In the Chinese approach, pain and illness are caused by blockages in these meridians. To relieve pain or illness, an acupuncturist inserts very thin, sterile needles into specific junctures on the pathways and twirls the needles to release the blockages and restore the balanced flow of chi.

Return to topTips for working with medications

Stick to a regular schedule. In an effort to minimize the amount of medicine they take, some people try to extend the interval between dosages. Unfortunately, it is much harder to bring pain back under control than it is to prevent it from flaring up in the first place. Deviating from the schedule suggested by the doctor can result in a need for more medicine to keep the pain in check than if each dose had been taken when prescribed. If you are having trouble remembering to give a dosage, use an alarm clock or the oven timer to help remind you.

Do not skip middle-of-the-night doses. Because the body needs a constant level of medication in the system, skipping a middle-of-the-night dose is likely to result in unnecessary pain. If getting up is too difficult for the patient, shift the schedule so the late-night and early-morning doses are closer to times when he or she is more likely to be awake.

Get instructions about breakthrough pain. Sometimes a patient will begin to feel pain before the next dosage is due. Generally it is better to administer a smaller dosage in the middle than wait until the next scheduled time. Again, it is easier to stop a buildup of pain than it is to correct it after the fact.

Ask your doctor what to do if the patient vomits up the medicine. Some medications can be re-administered if they were given only a few minutes beforehand. Others require that you wait a specific interval of time before it is safe to give them again.

Consider alternate forms of the medicine. If the patient is having trouble with middle-of-the-night doses, a patch might be a better way for the medication to be administered. If the patient is having trouble swallowing or is throwing up the medicine, a patch or rectal suppository might be a preferable delivery method. Check with your doctor before you crush a pill and put it in applesauce. Some medications do not work as intended if they have been crushed or altered.

Use a pill tray. Many people with a serious illness take an overwhelming number of medicines. To help keep track of the patient’s treatment schedule, purchase a pill tray that has compartments for morning, noon, evening, and night. Because many boxes hold up to seven days’ worth of medication, choose a time when you can fill the tray without distraction. Once the tray is full, simply give the medicines one compartment at a time. You will find that using a pill tray also helps verify when the patient last took his or her medication.

Call several days in advance for refills. It often takes a doctor a few days to get a refill prescription to the pharmacy. When the patient gets down to five days’ worth of medication, call the doctor for a refill. It’s better to be safe than sorry!

Use the same pharmacy for all the patient’s prescriptions. Many patients have several doctors. It is difficult for these physicians to know what their colleagues have prescribed. Let the pharmacist help you avoid negative drug interactions. If all the patient’s prescriptions are filled at the same pharmacy, the druggist can alert you about combinations that are known to present problems.

Help monitor the pain. Keep a chart of the types of pain the patient is experiencing and when during the day the pain occurs. Help the patient rate the pain using a 0-to-10 rating system and record these numbers. The more information you can give the doctor about your loved one’s condition, the more likely it is that your health provider will be able to combat the pain.

Take periodic time away for yourself. It’s not selfish, it’s essential! Caring for a person in chronic pain can be very draining. If you do not take breaks now and then, you are likely to burn out and will not be able to give the best care possible. Check with community agencies, friends, family, or your congregation for help with respite. A simple walk around the block or lunch with a friend can do wonders for your mood and your ability to keep giving optimum care. You need to keep your strength up, if not for yourself, then for the sake of the patient.

Return to top