Family Caregiver Connection

Helpful tips for family caregivers

July/August 2012

As a family caregiver, you have lots to juggle. Here are resources to make it easier.

How to beat "decision fatigue"

Caring for an ill family member often requires taking on the role of “decision maker.”

Caring for an ill family member often requires taking on the role of “decision maker.”

Sometimes it’s multiple mundane decisions (Should you ask your sister to do the shopping? Is this a good day to shower Mom? Now or after lunch?). And sometimes it’s several important health decisions, all in a short period of time.

Every decision is brain work

Decision making involves considering options and looking at tradeoffs, and then making a choice. Research has found these are particularly demanding mental tasks. So when you have a lot of decisions to make over the course of a day, your brain gets weary. That is called “decision fatigue.”

Decision fatigue affects our behavior

You are unlikely to feel your brain’s fatigue; it’s not like physical fatigue. But weary brains, like weary bodies, get lazy. In fact, a weary brain resists expending all the energy that is required to make a careful decision. Instead, researchers report, when we are mentally fatigued we resort to shortcuts: we make choices quickly and impulsively or we make no choice at all.

With that kind of decision making, we’re likely to have regrets later (even “no choice” has consequences).

Set the stage for good decision making

We can all make sound decisions. It isn’t about how smart you are. It’s about ensuring your brain is primed for the task.

- Early is better. Make important decisions before fatigue sets in. For example, try to schedule important meetings or doctor appointments early in the day.

- Food is fuel. Food sends glucose to the brain, and that helps restore quality thinking any time of day. Aim to make decisions after a meal or a nutritious snack.

- Routine is wise. Establish a schedule for as many routine tasks as possible. That saves your brainpower for decisions that are truly important.

Return to top

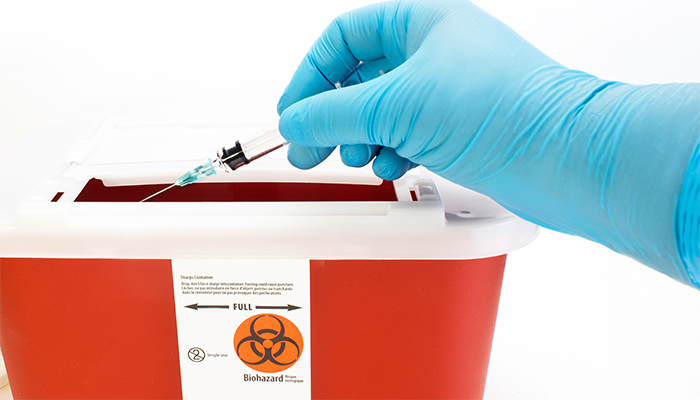

Safe disposal of "sharps"

Home management of a chronic illness often requires the use of needles or lances. You may need to give your family member shots. Or draw drops of blood for testing.

Home management of a chronic illness often requires the use of needles or lances. You may need to give your family member shots. Or draw drops of blood for testing.

All these procedures involve the use of what are known as “sharps.”

- Needles, infusion sets, and other systems for giving drugs or withdrawing fluids

- “Fingerstick” instruments for getting drops of blood

- Insulin pens and other prefilled devices for drug injection

The EPA estimates that every year more than 3 billion sharps are used in homes and other nonmedical settings.

A used sharp is a danger to people and pets. They can cause injury, creating an opportunity for infection. And they can spread diseases such as hepatitis and HIV.

- Never place loose sharps in a home or public wastebasket.

- Never flush sharps down the toilet.

If you poke yourself with a sharp, immediately wash area with soap or apply rubbing alcohol. Then call your doctor.

Always use a disposal container. Place used sharps in a container right away. If no container is available, recap the sharp for later disposal (be careful not to poke yourself in the process of recapping!). Leave containers only 75% full.

- FDA-approved containers. They are widely available online and through drugstores and medical supply stores. They are premarked with a “full” line. Some insurance plans and drug manufacturers pay for these containers.

- Alternative disposal containers. When necessary, use a heavy-duty, plastic household container. It should stand upright and have a tight-fitting lid with a small access hole. An empty liquid laundry detergent container is a good example. Label it clearly as containing hazardous waste.

Do NOT place a sharps container in the trash! Find out about container disposal options in your community from a local pharmacist, waste removal service, or city/county health department.

Return to topWhat is "assisted living"?

There are many options for older adults who can no longer live at home independently.

There are many options for older adults who can no longer live at home independently.

Assisted living facilities (ALFs) are tailored to individuals with health concerns that do not require the 24-hour medical attention provided by a nursing home. ALFs enable residents to be freed from the chore of meal preparation and housework and be supported in those activities that are challenging. They also offer social opportunities.

The majority of residents are age 85 or older, and female. Forty-two percent have some form of dementia.

The average ALF houses thirty-nine residents, although there is a wide range, from ten to more than one hundred. According to the National Center for Assisted Living, 56 percent of ALFs are part of a chain with two or more communities. Forty-two percent are independently owned.

ALFs typically provide these services:

- Private “apartments” for each resident. Usually studio or one bedroom. Most include a bathroom and kitchenette. Microwave ovens are usually available. Stoves are not.

- Meals with others. In most cases, residents gather in a common dining hall for three meals a day.

- Activities and a common area. Lounge areas are available for social interaction. Some facilities have exercise programs. Others offer music or field trips.

- Housekeeping, laundry, and a van service to nearby shopping centers.

- Security and supervision. Call buttons provide 24-hour access to staff as needed.

Smaller facilities may have fewer features.

Personal care services are provided when needed.

- A personalized care plan is developed for each resident.

- Help can be provided with managing medication. Also with such tasks as bathing and dressing, or walking to the dining room or to social activities. Additional fees are charged for these services.

- Residents are reassessed periodically to ensure needs are met.

Nonmedical assistants provide most of the daily hands-on care. ALF staff may or may not include a nurse to manage residents’ medical needs.

Medicare does not pay for the cost of an ALF. Some long-term care insurance policies allow for coverage of ALF fees. Veterans who qualify for the Aid and Assistance benefit may also apply this for an ALF. Talk to the facility in question and the insurer. As a general rule, facility fees must be paid with personal funds.

Return to top